What Do These People Have in Common?

Coaches in Action

They all have - or had - attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. In the workplace, the characteristics that these individuals display can drive you crazy, but they are not without their strengths

Saturday, March 03, 2007

Linda Walker would like to tweak your perception of some of the people you work with. If your organization is representative of the general population, you probably have a few co-workers who have attention deficit disorder (ADD) or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). And it's a safe bet that some of them drive you crazy.

But Walker, a St. Laurent-based coach who helps people with ADD/ADHD cope with the workplace and, by extension, life, wants you to know that the very characteristics ADHDers display that can drive you nuts, can be assets in your organization.

"A lot of ADHDers have their own way of doing things," Walker said.

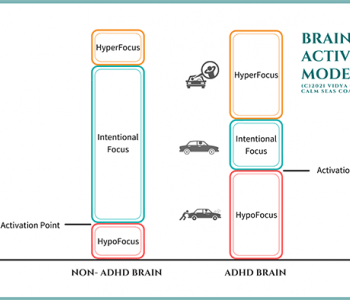

For the record, ADD/ADHD is a complex neurological disorder that affects the brain's hardwiring.

"ADHDers' brains are different," Walker said. "ADHD has no effect on intellect but ADHDers have a sense of internal agitation. They hear and feel all stimuli and have a hard time inhibiting those stimuli."

That's why they're easily distractible, she said.

In fact, they display a constellation of characteristics.

"They procrastinate," Walker said. "They start projects without finishing them. They have difficulty with time management so they're often late. They have difficulty starting tasks that don't interest them because the brain cannot ignite. It's not because they won't; it's because they can't. They're also impatient and want to get things done quickly."

Because their brains are unable to tune out extraneous stimuli, it's often difficult to focus on a single task, she said.

Another key characteristic of ADD/ADHD is a lack of impulse restraint.

Walker, who has had a succession of careers, began studying ADHD after her own daughter, now 18, was diagnosed with it at the age of 5.

"She's very hyperactive," she said. "We started reading about it and realized my husband, Duane Gordon, is also ADHD."

Gordon, however, had not been diagnosed in childhood, and Walker cites his impulsivity as a problem in their marriage.

"He was an impulsive spender," she said.

Once Gordon got an ADHD coach to help him, life improved immensely, Walker said.

"Because of coaching, he ended up getting a promotion at work and it has made a big difference in our home life."

Gordon's experience was the catalyst that made Walker get training at the ADD Coach Academy in Albany, N.Y., and she's been coaching ADD/ADHD adults since.

She believes the workplace is not always understanding of workers with ADD or ADHD.

"Our society is set up to work with linear thinkers."

Her workshops and one-on-one coaching sessions are designed to give her clients strategies for the workplace.

Because time management can be a problem, she helps her clients prioritize their tasks. One man discovered that his most productive hours were in the early morning.

"I encouraged him to book the time when he would check his voice mail and email. So he started work at 7 a.m. and would get four hours of work done before checking his email. Some of his colleagues complained to his boss that he didn't answer email before 11 a.m., but his boss sided with him because those four hours were very productive."

She encourages clients to recognize when their peak energy level occurs during the workday.

"Once they recognize that, they learn when their best work time is. Ideally, you book work that requires the most focus for that time.

"I have clients who work best in the middle of the night because they have difficulty sleeping."

She says many ADHD adults do not handle details well.

"It's a problem for ADHD managers who lack support staff to juggle detail work," she said.

Cube farms can also be a problem because of the prevalence of distracting sounds.

"I know of a lot of ADDers who can work while listening to music and so they wear earphones in their cubicles," she said.

The good news, Walker said, is that the very characteristics that can make worklife a challenge for ADHD adults in structured organizations can also be a boon for employers and ultimately, the economy.

"They're risk takers and so are more likely to go into entrepreneurship," she said. "Some have great ideas and don't have an opportunity to get those ideas across when they're employed in a company."

Consider, for instance, the fact that billionaire Sir Richard Branson, founder of the Virgin record and airline empire, has ADHD. Ditto for David Neeleman, founder of JetBlue Airlines and inventor of the e-ticket.

Walker says it's important for employers to understand that the ADHDers in their workforce might arrive at their work goals differently from their colleagues.

"The 'how' of how an ADDer does the work is not important," she said. "What they get done is important."

And what they get done can be formidable, she added.

"They can often get people going and help others to see the big picture. So if you have a project manager who is non-ADD and who likes details, such as doing the budget, but doesn't really like dealing with people, consider pairing him with an ADDer who can get people going but can't handle details. They complement each other."

Walker says certain roles, like police officers and ambulance attendants, attract ADHDers because of the risk factors.

Enlightened employers seek out the strengths in their ADHD staffers and help them to develop, she said.

Many clients who hire her for coaching initially seek out her services "because they just want to handle life."

She urges them to play to their strengths rather than focusing on their shortcomings.

In fact, successful ADHDers throughout history have done just that, she said. They include Leonardo da Vinci, Winston Churchill and Thomas Edison, to name but a few.