Attention Deficit Is in the Office, Too

ADDCA In The News | ADHD Education

New York Times

Business Section

Executive Life

By Anne Field

Click Here

Two years ago, Andrew Hearn felt as if he was going nowhere fast. He was 45 but couldn't hold down a full-time job in his field, social work, instead doing part-time stints at Planned Parenthood of New York City and Beth Israel Medical Center.

Deficit Disorder Association. One of her clients, the chief executive of an insurance company in the Midwest, sought her out at the urging of his family.

His symptoms were classic. He would change appointments without telling his assistants, lose files, run meetings without an agenda, jump from topic to topic and generally leave everyone in confusion. "It was like trying to lasso an amoeba," Ms. Ratey said. But his condition was treatable. Ms. Ratey followed him around for three days, interviewing people including his chauffeur and his secretary, then made recommendations. Each morning, for example, his assistant would hand him one file at a time, discussing what needed to be done and taking notes. Only after they had finished with one folder would she hand him the next. The chief executive also moved his top executives' offices closer to his own, so he would have fewer distractions on his way to talk to them.

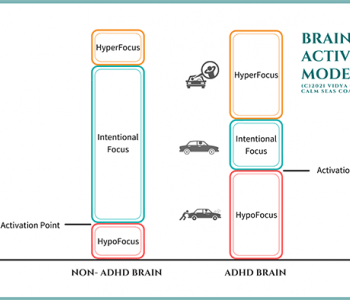

Difficulty in concentrating is probably the most troublesome symptom for executives and is the focus of most coaching. Pamela Redmond, executive director for finance operations at Anthem Inc., an insurance company in Columbus, Ohio, is a case in point.

Ms. Redmond, 46, had managed to succeed in her job despite her lifelong pattern of being easily distracted and her difficulty juggling multiple assignments. But there was a cost. "For years, I'd watch other people leaving at 6, and I'd be there till 9, 10 at night," she said. "I just wasn't able to focus." Thirty people reported to her, and she had meetings throughout the day.

Ms. Redmond suspected that she had A.D.H.D., though she didn't take a diagnostic test. Instead, a year ago, she sought help from Barbara McCrae, a coach in Colorado Springs. In weekly phone sessions — executive coaching is often done on the phone — the two zeroed in on ways to bolster her organizational skills. For example, she learned how to make a to-do list that wasn't "just 100 things I needed to get done," she said. She learned techniques for figuring out which two or three tasks were the most important and started keeping a journal about her goals. Today, she says, she leaves the office around 7, even during her busiest season.

Coaching techniques vary. A daily nagging session works for a 54-year-old Massachusetts executive who requested anonymity. For the past year, his coach has been making 10-minute calls every morning at 8 to go over the previous day's accomplishments and the goals for that day.

"It's all about time management," said the executive, who recently left his old job as the principal of a consulting firm to become director of policy for a state agency.

Executives can learn a variety of on-the-job strategies, but the most important coping mechanism is finding good office help, coaches say.

"The things that are hard for them, they need to delegate," Ms. McCrae said. "And they have to get a very organized assistant."