Is it ADHD that’s Eating the Boss?

ADDCA In The News | ADHD Education

London Times on-line

Good job? Can’t concentrate? Lost your keys? Then you may have ADHD, which, as Abigail Rayner reports from New York , is no longer suffered only by children

EVERY TIME Lauren Webber, a 49-year-old sales manager from Boston, left his house, he had to go through the same frustrating ritual of trying to find the keys or mobile phone he had been holding in his hands only minutes before.

“What did you do with my car keys, where’s my phone, what are you people doing?” he would accuse his wife Frances and sons Elijah, 14, and Gabriel, 10. “I’d get very angry and impatient because I was always late for everything,” Webber, pictured right, recalls.

There is nothing in the familiar family picture of early-morning chaos to suggest that Webber’s experience was remarkable. But then, just under two years ago, he was diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

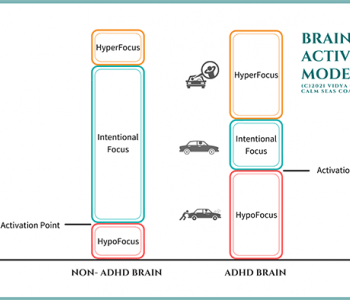

ADHD is a condition that conjures up the image of small boys unable to sit still in school. But according to the 2003 National Comorbidity Study (led by Ronald Kessler, professor of healthcare policy at Harvard Medical School ), as much as 4.4 per cent of the adult US population carries the syndrome into adulthood. This means that a significant proportion of the population is struggling to deal with daily life, both at home and in the workplace. They are easily distracted and cannot complete tasks. They can also be highly creative, and according to some experts the condition is common among high-powered executives.

It was only when ADHD was diagnosed in his son that Webber, a financial analyst, recognised that he, too, might have the condition. It is quite common for adults to discover that they have ADHD during a child’s assessment, says Dr Albert J. Allen, an ADHD specialist who works for the pharmaceutical company Eli Lilly. “ADHD is one of the most heritable conditions we know of.”

Almost two years on, Webber feels like a new man. He now takes Concerta (manufactured by Johnson & Johnson), a stimulant commonly used to treat ADHD, and hasn’t lost his keys since he started his course. His business is flourishing and he hopes to make it a full-time venture.

Adults diagnosed with ADHD represent a potential boon for the pharmaceutical industry. The market for ADHD, currently worth $2 billion (£1.1 billion) and composed mostly of children, could swell to $10 billion with adult prescriptions. Eli Lilly, whose own product, Strattera, was launched in January 2003 and is advertised with a slick television commercial featuring a typical modern noisy family home, insists that it is only raising awareness.

However, the emergence of ADHD as an adult illness is regarded by some with scepticism. There is already controversy surrounding its diagnosis among children. “Some people have expressed concern that it has been overdiagnosed,” Dr Allen concedes. “But I would argue that it is underdiagnosed.”

If Kessler’s findings are accurate, nine million adults in the US have ADHD. However, only 15 per cent of them have had the disease diagnosed. The rest remain unaware, possibly struggling to get along in life. Lenard Adler, the director of the combined adult ADHD programme and associate professor of psychiatry and neurology at New York University , says the reason ADHD is regarded with suspicion is that its symptoms are so familiar. Diagnosis is made only if the symptoms are disrupting the person’s life in two or more realms. ADHDlike symptoms can also be caused by overwork or another illness, such as depression.

ADHD experts are anxious to dispel the idea that it is a phoney illness, partly because of the devastating consequences it can have in the world of adults. In studies carried out on adolescents, those with ADHD were found to have more road accidents; they would tend to speed and quickly became impatient, failing to wait at stop lights. “They are more likely to get sexually transmitted diseases,” Dr Adler adds. “It is not clear why — it is just something that has shown up in statistics.”

One possibility is because they are impulsive. The condition is apparently common among high-powered executives. The rapid pace of their minds is suited to the multi-tasking role, and orderliness is delegated to a battery of assistants.

According to Dr Allen, ADHD sufferers “often have very high selfesteem. They say that it explains their creativity.” He recalls treating a successful executive who wasn’t suffering any difficulties but others were at their wits’ end because of his suspected ADHD. “His wife and the assistant talked often because the assistant was constantly bringing her up to date on his whereabouts.”

Jennifer Koretsky is an ADHD coach in New York ; she charges $110 an hour, or $340 for a four-week package, to teach people with ADHD how to manage their lives. “It can mean teaching people ways to avoid the subway at rush hour, because it is a sensory overload for ADHD sufferers — some people are spent before they even get to work.

Koretsky herself has ADHD. She had a successful job in marketing and at 25 had earned enough to buy her own apartment in the city. But she still felt that she wasn’t achieving to her full potential: “I wanted to get out of corporate America and help people. I didn't think my job was very meaningful." She was always late to work and to meetings, and there was never any food in her house.

Her therapist sent her to a psychiatrist, who diagnosed ADHD. Not long after, she took a nine-month course at the ADD Coach Academy in New York . There is no formal qualification for Koretsky's coaching. She employs two coaches herself, one for her ADHD and one for business development. She sees no irony in the arrangement. "People with ADHD are very driven if we want something very creative and compassionate," she says.

For Thom Hartmann, a wellknown American author and commentator, ADHD is not a disease or a disorder but merely a difference in the way people think. When ADHD was diagnosed in his son, Justin, he came up with a metaphor to describe the child's mind.

Justin, then 13 and a budding biologist, was devastated when a doctor told him he had a "brain disease" and would never go to college. Hartmann chose to explain it differently: he told Justin that the world was made up of hunter-gatherers and farmers and that 100,000 years ago the huntergatherer was vital to sustain humankind. He was prepared to risk his own life to get food and he was easily distracted by things, making him a good hunter and guard. As the world evolved and many of the risks were eliminated, the need for the hunter type diminished. He explained to Justin that he was "a hunter - and the world has been taken over by farmers. You can learn to be a farmer or you can take farmer pills."

What had started out as a metaphor was later backed up with science. Jay Fykes, a cultural anthropologist, found that the theory was exhibited in the different ways that American Indian tribes had evolved: "The Athabaskan are displaced hunters: give them a spear and a horse and they ruled the world, but when they tried to live in boxes and drive around in boxes and work in boxes, their society fell into crisis. The Pueblos had always been a thoughtful, fairly well-organised society and they did pretty well in modern America ."

A couple of years ago Dr Robert Moyzis, of the University of California in Irvine , found that early human beings with ADHD traits were more likely to survive. The traits were associated with the DRD4 7R gene that is present in about half of ADHD individuals.

Many other ADHD experts have disagreed with Hartmann's theory, but they agree that the syndrome does exist in adults and cannot be ignored. "This is a disorder that is real. There are real consequences to overlooking it," says Dr Adler.